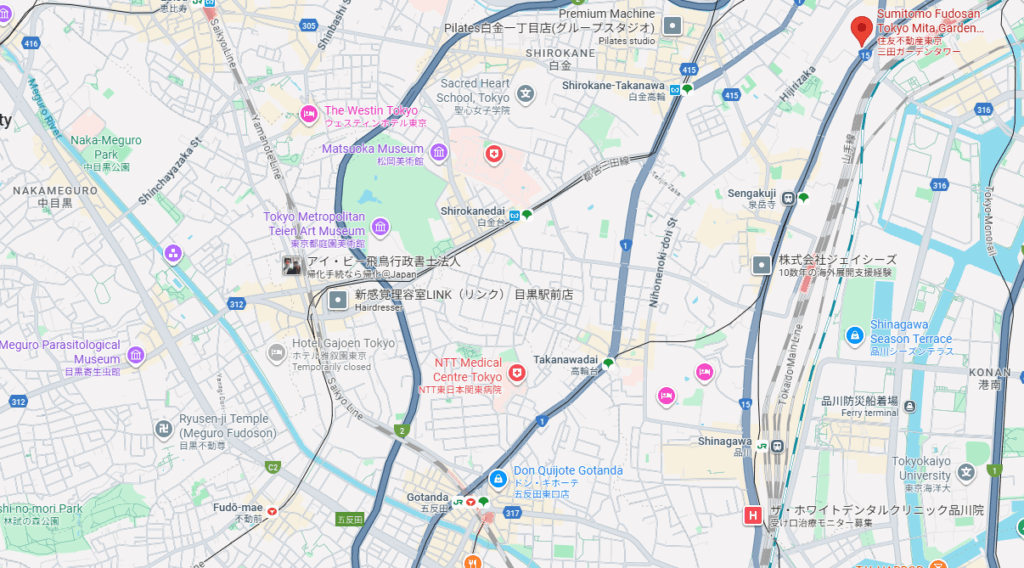

Chapter 1 — Choosing the Land

When building a home in Japan, the very first decision that determines everything that follows is the choice of land. Beautiful scenery or a convenient location may look appealing, but what truly defines the value of a property is its stability—legal, environmental, and structural.

1. Local Ordinances and Zoning

Every municipality in Japan has its own local ordinances (jōrei) that define how a property can be developed. Before purchasing, verify the zoning category (yōto chiiki) assigned to the lot. For residential use, areas designated as “First” or “Second Low-Rise Residential Zone” are generally best for long-term peace and good sunlight. Commercial or mixed zones allow taller buildings, which may affect privacy and brightness in the future.

2. Surrounding Environment and Sunlight

Sunlight and quietness are irreplaceable once construction is complete. Inspect the surroundings carefully to ensure that tall buildings or structures do not block southern light. Observe noise levels during morning, evening, and weekend hours, as well as wind direction and the presence of odors from restaurants or factories.

3. Land Conditions and Infrastructure

Request written confirmation of the lot’s road width, utility access, and ground condition. If the front road is narrower than 4 meters, a portion of the land may need to be “set back” for road widening. Confirm that water, gas, and sewage lines already reach the property. If not, connection work can cost several hundred thousand yen or more.

4. Soil and Structural Safety

The apparent flatness of the land does not guarantee solid ground. Soft soil requires reinforcement through pile driving or ground improvement, which can add several million yen to total cost. Always obtain a geotechnical survey report before signing any contract. Even new developments may have hidden fill layers that increase subsidence risk.

5. Legal Boundaries and Measurement

Never rely solely on fence lines or visible markers. Ask for a certified survey map (kakutei sokuryōzu) prepared by a licensed surveyor. Check whether all boundary points are agreed upon with neighboring owners. If the lot lacks a confirmed boundary, expect delays in registration and possible disputes later.

6. Future Risks and Development Plans

Investigate the surrounding area’s urban planning map for any future road expansion, railway projects, or high-rise construction. Even a quiet neighborhood can change drastically once new zoning is approved. Ask the city’s planning division to confirm whether your lot or adjacent parcels are included in redevelopment zones.

7. Combined Land and Building Sales

In Japan, land and building transactions are often treated as one package. Be cautious when an agent says “total price,” as it may only cover the building itself. The land may still require separate registration or financing. If purchasing land first and constructing later, make sure to budget for bridge financing (tsunagi yūshi) and temporary taxes incurred during that period.

8. Decision Criteria

- Zoning and building restrictions confirmed in writing

- Southern sunlight unobstructed by existing or planned buildings

- Utilities (water, gas, sewage) available and connection costs known

- Soil report obtained and improvement budget secured

- Certified survey map completed and boundaries agreed upon

- No major redevelopment or new road plan nearby

Choosing land is not about finding what looks ideal today, but securing a foundation that will remain stable for decades. In Japan’s dense cities, sunlight, quietness, and legal certainty are what truly define a home’s value.

Chapter 2 — Sunlight, Wind, and Environmental Balance

Even a well-designed house will fail if sunlight and airflow are ignored. In Japan’s dense urban environment, the positioning of your home relative to its surroundings determines whether you live in brightness or shadow for decades. Sunlight is not a luxury—it is a structural condition that shapes both comfort and energy performance.

1. The Importance of Southern Exposure

In Japanese architecture, south-facing living rooms and windows are the foundation of comfortable design. The sun moves low in winter and high in summer, making orientation crucial. Confirm that the south side of your lot remains open and not shaded by neighboring buildings or trees. A narrow road or tall wall directly to the south can permanently reduce natural light inside the house.

2. Daylight Simulation Before Design

Before construction, request a sunlight and shadow simulation (hiei-zu) from your architect or builder. It visually predicts how sunlight enters each room through the year. If you find that a key area—such as the living room or studio—receives less than two hours of direct sunlight during winter solstice, consider revising the plan or increasing window height.

3. Window Placement and Heat Control

Large windows should face south or east. Avoid large western windows unless protected by eaves or blinds, as they cause overheating in summer. Install Low-E double glazing to maintain insulation and reduce condensation. For Calliope’s studio-type layout, fixed south windows combined with side vents provide bright yet quiet conditions.

4. Ventilation and Wind Path

Natural airflow reduces humidity, odor, and heat accumulation. In design terms, this means creating a cross-ventilation path between the south and north sides of the house. If the site is narrow, high windows or roof vents can act as air outlets. Mechanical ventilation alone cannot replace the comfort of moving air.

5. Noise and Air Quality

Wind can also carry sound and odor. Before finalizing a site, check the wind direction and strength—especially if close to main roads or restaurants. In Tokyo’s 23 wards, northwesterly winter winds are common; in summer, southerly sea breezes dominate. Understanding these patterns helps decide where to place windows, balconies, and air intake vents.

6. Thermal Envelope and Moisture Control

Sunlight and wind relate directly to energy balance. Properly oriented windows and vents reduce air-conditioning costs by 20–30%. Use external shading instead of curtains to control summer heat, and keep eaves around 600 mm for effective solar cutoff. In humid regions, include ventilation layers behind exterior walls to prevent condensation and mold.

7. Environmental Harmony

Good sunlight and wind conditions are not only functional—they form part of the home’s atmosphere. Light that changes through the day adds rhythm to life. A window that catches the evening breeze can do more for comfort than expensive materials. Architecture begins with the invisible: air, light, and sound.

Chapter 3 — Home Loans for Foreign Residents

Buying land and building a new home in Japan is possible even for non-Japanese citizens, but the financial process differs greatly from other countries. Japanese banks evaluate long-term stability rather than potential income. For creators or self-employed residents, preparation and documentation determine success.

1. Understanding How Japanese Banks Evaluate You

Japanese lenders rely heavily on official documents rather than conversation or reputation. They will carefully check your visa type, tax history, and proof of income. Even if you earn well, a short-term visa can limit loan duration. In principle, the repayment period cannot exceed your remaining visa term.

2. Self-Employed Creators and Taxable Income

For individual creators like Calliope, the most important figure is not total earnings, but taxable income after expenses. A high expense ratio reduces the income shown on tax documents, which lowers borrowing capacity. Banks see what is written on your tax certificate (kazei shōmeisho) — nothing more.

3. Required Documents for Application

- Certificate of residence (jūminhyō) showing current visa status

- Tax certificate from the local tax office (latest 2 years)

- Bank statements showing savings and payment history

- Proof of income in yen equivalent if paid in foreign currency

- Copy of your employment or contract with COVER Corp (or management entity)

4. Choosing the Right Bank

Each institution has a different stance toward foreign borrowers. The Japan Housing Finance Agency’s “Flat 35” program accepts foreign residents but requires stable tax records and permanent address in Japan. Private banks like Shinsei Bank, SMBC Trust Bank PRESTIA, and Tokyo Star Bank tend to be more flexible and English-friendly.

5. Down Payment and Savings Strategy

Most banks require a down payment of 10–20% of the total project cost. Paying the entire amount in cash is possible but not always wise. Unexpected expenses such as moving, furniture, or small construction changes can appear suddenly. It is safer to keep at least three to six months of living costs in reserve.

6. Bridge Financing Between Land and Construction

If you purchase land first and build later, you will need bridge financing (tsunagi yūshi) to cover costs before the main loan begins. This temporary loan bridges the period between land payment and building completion. Confirm the interest rate and repayment timing in advance, as these are often higher than regular mortgage rates.

7. Credit and Communication Tips

- Always use the same bank account for income deposits to prove stability.

- Keep clear transaction history in yen, not only in foreign currency.

- Prepare a simple written explanation (in English and Japanese) of your work and income system.

- Bring a bilingual interpreter experienced in real estate finance — not just a casual translator.

8. Realistic Timeframe

From document preparation to final approval, expect two to three months if all paperwork is consistent. If you lack a permanent visa or long tax history, approval may take longer. Patience and accuracy matter more than speed.

9. Key Takeaways

- Loan terms depend on visa length, not nationality.

- Taxable income decides the maximum loan amount.

- Keep clear proof of income and residence in Japanese format.

- Always reserve cash for unexpected costs after purchase.

- Ask about bridge loans before signing any land contract.

Financing a home in Japan requires discipline, but it is not impossible. The key is to understand how the system views risk — and to show that you have already planned for stability.

Chapter 4 — Real Estate Contracts and Intermediaries

In Japan, a real estate contract is not just paperwork — it is a legal statement that binds buyer, seller, and agent under the Civil Code. Foreign buyers often assume that the agent represents them, but in reality, the agent’s primary duty is usually to the seller. Understanding this relationship is critical before signing anything.

1. Agency Structure in Japan

Real estate agents in Japan operate under a dual-agency system. This means a single agent can represent both buyer and seller, collecting fees from both sides. While legal, this system can create conflicts of interest. As a foreign buyer, you must always confirm whether your agent is acting as:

- Exclusive buyer’s agent — represents your interests only

- Dual agent — represents both sides (most common)

- Seller’s agent — prioritizes the seller’s profit

Ask the agent directly: “Who are you representing in this deal?” If they hesitate, that is already a warning sign.

2. The Importance of the Explanation of Important Matters (Jūyō Jikō Setsumeisho)

Before signing any purchase agreement, Japanese law requires agents to deliver an official document called the “Explanation of Important Matters”, issued and signed by a licensed takkenshi (real estate transaction specialist). This document defines zoning, rights, boundaries, and all legal conditions of the property. Foreign buyers should never skip or rush this process.

Request the English translation or have a bilingual architect review the document. Pay special attention to the following sections:

- Land ownership type (freehold or leasehold)

- Legal restrictions (setback, building coverage ratio, floor area ratio)

- Right-of-way and easement clauses

- Earthquake resistance, flood hazard zone, and construction year

- Warranty clauses and defect liability period

3. When to Bring a Bilingual Expert

Do not rely solely on the company’s translator or sales agent. Hire a bilingual architect or real estate consultant who understands both construction and legal terminology. They can explain not only what the document says, but also what it implies. A 30-minute pre-contract review by an independent expert can prevent years of trouble.

4. Deposits and Payment Structure

Once a purchase agreement is signed, the buyer typically pays a deposit (shokikin) of 5–10%. If the buyer cancels without legal reason, the deposit is forfeited. If the seller cancels, they must return double the deposit. Always confirm the conditions for cancellation in writing — not verbally.

For construction contracts, payments are often divided into three stages:

- 1st payment: upon signing (land and design confirmation)

- 2nd payment: during construction (mid-stage check)

- 3rd payment: after completion and inspection

Never make full payment before the final inspection is completed by an independent third-party architect.

5. Typical Hidden Clauses and How to Read Them

Some Japanese contracts use vague terms that can shift responsibility to the buyer. Be cautious of the following phrases:

- “After adjustment upon confirmed survey” — may lead to additional land cost.

- “Minor changes allowed” — allows design or material changes without your approval.

- “Other related costs” — may include undefined management or administrative fees.

Mark any unclear clause and request written clarification before signing. Do not rely on “verbal promises” — they hold no legal weight in Japan.

6. The Role of Electronic Contracts

Since 2022, Japan legally recognizes electronic real estate contracts. Signatures are conducted through certified e-sign systems that include timestamps and audit logs. This is convenient for foreign residents, but ensure that all PDFs include the agent’s license number and corporate seal data.

7. Final Checklist Before Signing

- Confirm agency relationship in writing (who the agent represents)

- Obtain the English summary of “Explanation of Important Matters”

- Ensure all payments and deposits are traceable through bank transfer

- Ask an independent bilingual architect to review key clauses

- Verify cancellation and warranty terms in both languages

8. Key Principle

A real estate contract in Japan is not about trust — it is about clarity. The more precise your written terms are, the less you will depend on verbal interpretation later. Treat every signature as an architectural decision — once fixed, it shapes everything built upon it.

Chapter 5 — Independent Building Inspection: Choosing the Right Expert

The most dangerous mistake when building a house is trusting the contractor’s own inspection reports. A “completion certificate” issued by the builder is a self-declaration, not a legal guarantee of quality. For any foreign homeowner, hiring an independent, third-party architect is essential. Their job is to verify what is actually built, not what was promised on paper.

1. Recommended Inspection Phases

An independent inspector should examine the structure at every critical stage of construction. The goal is not to catch the contractor doing something wrong, but to document the house as it is truly built — in both Japanese and English.

- Foundation Inspection: Rebar thickness, concrete cover, waterproofing layer

- Structural Frame Inspection: Columns, beams, shear walls, metal connections

- Waterproofing & Finishing Inspection: Roof, balcony, ventilation layers, wiring

At each stage, require a photo-based bilingual report signed by the site supervisor. Store both paper and electronic copies; these documents will serve as proof for insurance and warranty claims later.

2. Criteria for Selecting an Architect or Inspector

| Criteria | Recommended Standard |

|---|---|

| Qualification | First-Class Architect or Structural Engineer |

| Experience | 10+ years of housing inspection and English reporting experience |

| Affiliation | Independent architectural office with no financial ties to the builder |

| Typical Cost | ¥150,000–¥250,000 (3 inspections + report) |

Whenever possible, choose a bilingual architect. If the drawings, contracts, and inspection reports are organized in both Japanese and English, they will serve as solid evidence during any future repair or warranty discussions. What matters most is not how deeply you understand construction — but that it is explained in a language you fully understand.

3. Why a Third Party Matters

Japanese contractors often perform “in-house inspections,” but such reports naturally avoid highlighting their own mistakes. A third-party architect, independent from the builder, can detect structural misalignments, insufficient reinforcement, or poor waterproofing before they turn into costly problems. Once the building is complete, hidden defects become legally and physically difficult to fix.

4. How to Establish a Transparent Record

Each inspection report should include:

- Date and weather conditions

- Photos with detailed location captions

- Measurement values and test results

- Inspector’s signature and license number

- Summary in both Japanese and English

All reports must be compiled into a single PDF binder after construction completion. Keep a copy off-site (such as cloud storage). When warranty or repair negotiations occur, these bilingual records become your strongest defense.

5. Common Oversights and How to Prevent Them

- Never let the contractor choose the inspector — find one yourself.

- Confirm the inspector’s independence in writing (no subcontract ties).

- Ensure all technical reports are dated and signed.

- Ask for English explanations of any nonstandard materials or methods.

- Always store the inspection data in digital form with backups.

6. Key Philosophy

In construction, trust is not built with words but with documentation. A photograph taken before the concrete sets is worth more than a promise written after completion. Independent inspection is not about distrust — it is about accountability.

Chapter 6 — Warranty Systems: Ask Who Guarantees, Not Just What Is Promised

Most homebuyers feel safe when they see the words “10-year warranty” written in the contract. However, very few know who actually guarantees it or what is excluded from that coverage. In Japan, the true protection of a new house depends not on the contract itself, but on the insurance corporation behind it.

1. The Legal 10-Year Defect Liability

Under Japanese law, all new homes are covered by a 10-year defect liability (kashi tanpo sekinin) for the structure and waterproofing. This liability is not carried by the builder personally — it is insured by a registered warranty organization. If the builder disappears or goes bankrupt, the insurance company steps in to cover the cost of repair.

| Warranty Organization | Key Features |

|---|---|

| JIO (Japan Housing Warranty Organization) | Complies with the official “Housing Performance Display System” |

| Anshin Jūtaku Hoshō | Offers English documents and support for foreign clients |

| Jūtaku Anshin Hoshō | Covers reinforced concrete (RC) and steel-structure houses |

For a foreign homeowner like Calliope, choose a warranty provider that can issue English certificates. This allows you to make warranty claims or legal statements without depending entirely on Japanese intermediaries.

2. Extended Warranty (20–60 Years)

Many builders offer optional extended warranty programs. If you continue to take official maintenance inspections (usually every 5 or 10 years), coverage can be extended up to 20, 40, or even 60 years. However, these inspections must be performed by the builder’s designated company — not by yourself.

Important for custom designs like a rooftop studio or greenhouse: these features are often excluded from standard coverage. Before signing, ask the builder to clearly state:

- “Rooftop waterproofing, greenhouse, and studio sections are included in the warranty coverage.”

- “The extended warranty plan lists all covered parts with English translation.”

3. The Three-Party Agreement Model

The most reliable way to secure accountability is to create a three-party warranty agreement among:

- The real estate company (seller)

- The construction company (builder)

- The supervising architect (third-party inspector)

This structure ensures that, even if one party disappears, the others remain contractually responsible for warranty claims. It also gives the homeowner a direct channel to the insurance corporation through the architect’s certification.

4. How to Verify Coverage

- Request the full warranty certificate and its English summary.

- Check who the warranty issuer is (builder or insurance company).

- Ensure the warranty covers both structure and waterproofing.

- Ask whether optional features (roof deck, sound studio) are included.

- Confirm that all documents bear the insurer’s registration number.

5. Support Services for Foreign Homeowners

| Service Name | Provider | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Architects English Desk Tokyo | Independent Architects Association | Provides bilingual reports and on-site presence |

| House Inspection Japan | Certified First-Class Architects Team | English support with photographic and video documentation |

| Tokyo Building Safety Office | Tokyo Metropolitan Government | Free consultation on design applications and structural safety |

Use these services to translate complex warranty language into clear, actionable information. A warranty that you cannot read or confirm has no real value.

6. Core Principle

A contract defines what is promised. A warranty defines who stands behind that promise. Your goal as a homeowner is to make sure that someone will still answer the phone ten years from now.

Chapter 7 — The Hidden Pitfalls of Land and Building Package Deals

In Japan, land and building transactions are often presented as separate, but legally and financially they are tied together. For many foreign buyers, this structure is the source of major confusion — and sometimes, unexpected costs. Understanding the sequence of payment, loan structure, and contract responsibility is essential.

1. The “Package” System Explained

Builders and developers often promote land and building together as a “set price.” However, the construction company and the landowner may be different legal entities. This means you might be signing two contracts with two different parties — one for land, one for construction. Each has separate cancellation clauses, taxes, and obligations.

2. Bridge Loans and Timing Risks

When buying land first, you usually must pay the full land cost before the building is finished. Because a mortgage cannot be issued until the house exists, banks provide a bridge loan (tsunagi yūshi) to cover this gap. This temporary loan typically has a higher interest rate. If the construction schedule delays, you pay interest longer — even though you cannot yet live there.

3. Unclear Pricing and “Total Cost” Traps

Many buyers hear the term “total price” and believe it includes everything. In reality, it often covers only the main building structure. The following items are commonly excluded and billed separately:

- Utility connections (water, gas, electricity)

- Exterior work and landscaping

- Boundary survey adjustments

- Furniture, lighting, curtains, and air-conditioning units

Always request a detailed cost breakdown (meisai hyō) with English annotations. Never rely on verbal estimates or simplified leaflets.

4. Legal and Registration Issues

Even though the land and building are sold together, they require separate registrations (tōki). The land’s registration is handled at purchase, while the building’s registration occurs after completion. If ownership names differ between contracts, registration can be delayed — causing problems for the final loan release.

5. How to Protect Yourself

- Have both contracts reviewed by a bilingual architect or legal consultant.

- Confirm whether the land and construction companies are legally related.

- Check that both contracts list consistent property boundaries and floor area.

- Do not release the final construction payment until registration is confirmed.

6. Key Principle

In Japan, a house is not sold — it is assembled through multiple legal layers. Owning both the ground and the structure above it requires separate contracts and careful coordination. Without understanding this distinction, you may own neither completely.

Chapter 8 — Zoning, Ordinances, and Reading the Future of Your Neighborhood

Even the most beautiful house can lose value if its surroundings change. Before purchasing land in Japan, it is vital to understand zoning laws, local ordinances, and long-term development plans. These determine what can — and cannot — be built near your home.

1. Understanding Zoning (Yōto Chiiki)

Each area of Japan is classified into a specific use district. There are 13 main types, from residential to industrial zones. A plot located in a “Category I Residential Zone” may prohibit shops, bars, or workshops nearby. By contrast, “Category II” allows small stores or studios attached to houses.

2. Building Coverage and Floor Area Ratios

Two critical numbers appear on every land description:

- Building Coverage Ratio (Kenpeiritsu): The percentage of land that can be covered by the building footprint.

- Floor Area Ratio (Yōsekiritsu): The total floor space allowed relative to land size.

These directly control how large or tall your home can be. If Calliope plans a rooftop greenhouse or sound studio, the structure’s volume must remain within these limits.

3. Local Ordinances and Green Space Rules

Some Tokyo wards have greening ordinances that require gardens, planters, or trees on-site. Other districts restrict building height or roof color to maintain scenic harmony. Confirm whether your site falls under any of these rules before finalizing the design.

4. Predicting Future Surroundings

Use the city’s urban planning map (toshi keikaku chizu) to check if nearby land is marked for redevelopment. An empty lot next door could become a mid-rise apartment or commercial building in a few years. Choosing a corner lot or a south-facing road can help preserve sunlight and privacy over time.

5. Infrastructure and Noise Considerations

Check proximity to railways, schools, or restaurants. What seems convenient during the day can become noisy at night. If you plan to record or stream, ensure your lot is at least 30 meters away from major traffic routes.

6. Environmental Stability

Review hazard maps for flood, liquefaction, and earthquake zones. These are available on every municipality’s website. Avoid reclaimed or low-lying areas if long-term stability is a priority.

7. Key Principle

Land value is determined not by the present view, but by future risk. Zoning tells you what your neighbors can build tomorrow. Knowledge of local ordinances protects your sunlight, peace, and investment.

Chapter 9 — Integrated Studio Design: When the Home Itself Becomes an Instrument

For Calliope, a home is not merely a place to live — it is a vessel for creation. Designing a house that integrates music, recording, and streaming requires approaching architecture as if shaping an instrument itself.

1. Core Layout Principles

- Place the studio at the center of the house to minimize external noise from roads or wind.

- Separate its floor, wall, and ceiling structures using floating and decoupled designs.

- Include an air cavity (dead space) for bass absorption — structure defines sound.

2. Recommended Soundproof Specifications

| Component | Recommended Design | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Floor | Floating slab + vibration-damping rubber + dual subfloor | No rigid contact points |

| Walls | Double gypsum board + isolation bar + 50mm glass wool | Essential for adjoining rooms |

| Ceiling | Suspended ceiling with vibration hangers | Eliminates top-floor noise leaks |

| Windows | Double sash with acoustic Low-E glass | Include damping rails |

| Doors | Dual soundproof doors (T-3 rating) | Maintain pressure isolation |

3. Acoustic Design

Soundproofing is about silence; acoustics is about beauty. To balance both, use reflective and absorptive surfaces strategically.

- High-density absorption panels behind the performer

- Diffusion panels on side walls to prevent echo build-up

- Carpet or acoustic rug to suppress floor reflections

- Ceiling slope (1/10 gradient) to guide reflections backward

4. Air Conditioning and Ventilation

Silent air systems define comfort. Use low-vibration indoor units (under 20dB) and insulated ducts with silencers. Adopt vertical air circulation — ceiling intake and floor exhaust — to maintain fresh air while preserving acoustic stability.

5. Electrical and Noise Management

- Use a separate breaker panel for studio power lines.

- Dedicated earth grounding (under 10Ω) for audio circuits.

- Install EMI filters and analog dimmers instead of PWM controls.

- Use shielded LAN cables (STP) and isolated audio circuits.

6. Lighting and Atmosphere

The studio is not a silent box — it is a stage. Use high-CRI LED lights (≥90) with adjustable color temperature (2700–6000K). Integrate indirect lighting into acoustic panels, and control brightness remotely via DMX or Bluetooth.

7. Dimensions and Standards

| Element | Recommended Spec | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Studio area | 6–8㎡ | Optimized for solo work |

| Ceiling height | 2.6–2.8m | Reduces standing waves |

| Target reverb time | 0.25s ±0.05 | For clarity in speech and vocals |

| Noise criteria | NC-20 or lower | Professional-level silence |

8. Maintenance and Expansion

Replace absorption panels every five years. Clean air filters monthly. Reserve empty conduits (28mm) under the floor for future cable expansion. Longevity is built not through materials, but through maintenance discipline.

Chapter 10 — Buying a Home Means Designing a Life

Building a new home in Japan is not simply a financial decision — it is an act of long-term design. Every line drawn, every clause signed, and every choice of material will quietly shape your life for decades. For foreign residents, this journey is not easy, but it is deeply meaningful.

1. The Emotional Architecture

A home reflects its owner’s rhythm. When music, silence, and sunlight coexist, the space itself begins to breathe. Designing such a house requires not wealth, but patience — and a clear sense of what you truly need.

2. Financial Discipline as Architecture

Money is also a structural material. How you allocate it between land, construction, and future maintenance defines the house’s stability. A design that balances ambition and realism will always age gracefully.

3. Language and Culture

Building in a country where your first language is not spoken is difficult. But each meeting, each translated document, becomes part of the foundation of understanding. In that process, you are not only constructing walls — you are building belonging.

4. Final Thought

Calliope’s wish — to create a small sanctuary where butterflies may hatch — is not merely symbolic. It is what architecture should be: a bridge between the tangible and the delicate. When a house becomes both shelter and instrument, both studio and home, then creation itself has found a place to live.